Introduction

Vertigo is defined as “a condition in which somebody feels a sensation of whirling or tilting that causes a loss of balance.” To describe the sensation of vertigo, patients often use words such as dizziness, giddiness, unsteadiness, or lightheadedness. The neurological vertigo center is called the vestibular nucleus. The vestibular nucleus is located in the brainstem. It extends from the caudal portion of the pons through the caudal portion of the medulla.

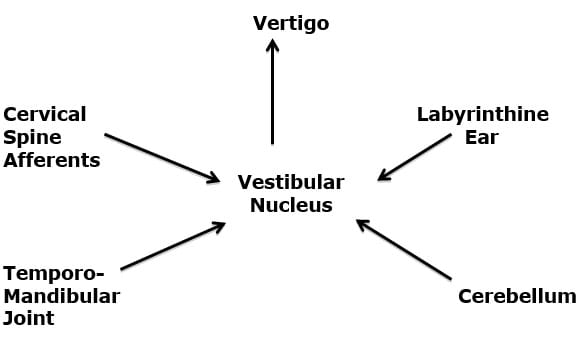

The afferent information that enters the vestibular nucleus to initiate the sensation of vertigo arises primarily from four sources:

1) Labyrinthine Inner Ear (1)

2) Cerebellum (2)

3) Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ) (3, 4, 5)

4) Cervical spine afferents, especially from C1 – C3 (6)

All health care providers should also be aware that vertigo could result as a consequence of vascular compromise of the posterior circulation of the brainstem (the vertebral and basilar arteries, and their branches) (7).

Pathology

The first study to link problems in the cervical spine to vertigo was published in the journal Lancet in 1955 (8). Today (October 12, 2015), a search of the National Library of Medicine with PubMed, using the words “cervical vertigo” locates 2,211 citations.

It was established in 1977 that the injection of saline irritants into the deep tissues of the upper cervical spine would create the sensation of vertigo in normal human volunteers (6).

Clinicians have documented a relationship between cervical spine trauma and the symptoms of vertigo (9). In her chapter titled “Posttraumatic Vertigo”, Dr. Linda Luxon (10) notes that this vertigo can be explained by “disruption of cervical proprioceptive input.” She notes that the major cervical spine afferent input to the vestibular nuclei “arises from the paravertebral joints and capsules, with relatively minor input from paravertebral muscles.” Dysfunctional upper cervical spinal joints and their capsules can alter the proprioceptive afferent input to the vestibular nucleus resulting in the symptoms of vertigo. Treatment would be to improve the mechanical function of these joints.

In 2001, an article appeared in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychology titled (11):

Cervical Vertigo

This article reviews the theoretical basis for cervical vertigo. These authors note:

“Proprioceptive input from the neck participates in the coordination of eye, head, and body posture as well as spatial orientation,” and this is the basis of the of cervical vertigo syndrome. Cervical vertigo is when the suspected mechanism is proprioceptive.

“Degenerative or traumatic changes of the cervical spine can induce altered sensory input causing vertigo.

“Dizziness and unsteadiness suspected to be of cervical origin could be due either to loss or inadequate stimulation of neck receptors in cervical pain syndromes.”

“Section or anesthesia of cervical roots or muscles causes an asymmetry in somatosensory input, unilateral irritation or deficit of neck afferents could create a cervical tone imbalance, thus disturbing integration of vestibular and neck inputs.”

“As somatosensory cervical input converges with vestibular input to mediate multisensory control of orientation, gaze in space, and posture, the clinical syndrome of cervical vertigo could theoretically include perceptual symptoms of disorientation, postural imbalance, and ocular motor signs.”

“A convincing mechanism of cervical vertigo would have to be based on altered upper cervical somatosensory input associated with neck tenderness and limitation of movement.”

“In summary, vertigo can be accompanied by cervical pain, associated with head injury, whiplash injury, or cervical spine disease.”

“If cervical vertigo exists, appropriate management is the same as that for the cervical pain syndrome.”

In 2002, an article appeared in the Journal of Whiplash & Related Disorders, titled (12):

A Cross-Sectional Study of the Association Between Pain and Disability in Neck Pain Patients with Dizziness of Suspected Cervical Origin

In this article, these authors state:

“The term ‘cervical vertigo’ was introduced to describe dizziness and unsteadiness associated with cervical spine pain syndromes.”

“Increasing evidence suggests that dizziness and vertigo may arise from dysfunctional cervical spine structures.”

“Whiplash patients are likely to suffer from dizziness, vertigo and associated neck pain and disability resulting from traumatized cervical spine structures.”

“Cervicogenic dizziness, especially in whiplash patients, may result from disturbed sensory information due to dysfunctional joint and neck mechanoreceptors.”

“Dizziness and vertigo are common complaints of neck pain patients with 80 to 90% of whiplash sufferers reporting these symptoms.”

“Dysfunction or trauma to connective tissues such as cervical muscles and ligaments rich in proprioceptive receptors (mechanoreceptors) may lead to sensory impairment.”

“Emerging evidence suggests that dizziness and vertigo may commonly arise from dysfunctional cervical spine structures such as joint and neck mechanoreceptors, particularly from trauma.”

In this study, the authors evaluated 180 consecutive neck pain patients over the age of 18 who were recruited from an outpatient clinic. Of these, 71 patients (40.57%) reported neck pain resulting from trauma and 60 patients (33.5%) were suffering from dizziness. Pain intensity was measured using the Numerical Rating Scale while disability was measured with the Neck Disability Index (NDI).

The authors note that dizzy patients also describe their symptoms with “lightheadedness, seasickness, instability, rotatory vertigo, etc.” Regarding dizziness, females were significantly more likely to report dizziness compared to males while no significant difference was found for dizziness versus age. Patients experiencing dizziness also reported greater intensity of neck pain compared to those without dizziness. Increasing duration of neck pain was significantly associated with increasing reports of dizziness. Subjects who reported dizziness were significantly more likely to have been involved in an injury. Neck pain patients with dizziness reported significantly more disability (total NDI score) compared to neck pain patients without dizziness.

The authors concluded that neck pain patients with dizziness were significantly more likely to have suffered a traumatic injury, experienced greater pain intensity and disability levels, and experienced for a longer period of time, compared to neck pain patients without dizziness.

This “study results reinforce the concept of neck pain and disability leading to cervicogenic dizziness/vertigo due to dysfunction of the somatosensory system of the neck.” The basic model presented in this article is that trauma causes “dysfunctional cervical spine structures” resulting in altered “joint and neck mechanoreceptor” function, causing both pain and dizziness.

In 2003, a group from the University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, published a study in the Journal of Rehabilitative Medicine titled (13):

Dizziness and Unsteadiness Following Whiplash Injury: Characteristic Features and Relationship with Cervical Joint position Error

These authors note that dizziness and/or unsteadiness are common symptoms of chronic whiplash-associated disorders, and that if the cervical spine injury is the suspected origin of these complaints that it can be assessed with “joint position error.” Joint position error is the accuracy to return to the natural head posture following extension and rotation. Consequently, these authors measured joint position error in 102 subjects with persistent whiplash-associated disorder and 44 control subjects. These authors found:

“The results indicated that subjects with whiplash-associated disorders had significantly greater joint position errors than control subjects.”

“Within the whiplash group, those with dizziness had greater joint position errors than those without dizziness following rotation.”

“Cervical mechanoreceptor dysfunction is a likely cause of dizziness in whiplash-associated disorder.”

“When there is no traumatic brain injury, abnormal cervical afferent input from damaged or functionally impaired neck joint and muscle receptors is considered the likely cause.”

Dizziness of cervical origin “originates from abnormal afferent activity from the extensive neck muscle and joint proprioceptors, which converges in the central nervous system with vestibular and visual signals, confusing the postural control system.”

These authors “contend that our results support a likely cervical cause of dizziness and or unsteadiness rather than other causes of dizziness in these subjects with persistent whiplash associated disorders and the joint position error findings highlight the role of cervical mechanoreceptor dysfunction.”

“The study highlights the role of cervical mechanoreceptor dysfunction and the importance of assessment and management of this impairment in persistent whiplash associated disorders, particularly in those complaining of dizziness and unsteadiness.”

These authors also noted that the most common words used were “lightheaded”, “unsteady” and “off-balance”. Other descriptions were clumsy, giddy, imbalance, motion sickness, falling/veering to one side, imbalance in the dark, vision jiggle (disturbance), faint feeling, might fall. Unsteadiness was the most common description, being stated by 90% of the subjects.

In 2012, neurological investigators from Buenos Aires, Argentina, and from the Chicago Dizziness and Hearing Center confirmed the existence and pathophysiology of post-traumatic cervical vertigo, and cervicogenic proprioceptive vertigo. Their article appeared in the journal Neurologia, and is titled (14):

Cervical Vertigo:

Myths, Facts, and Scientific Evidence

These authors note that aspects of “cervical vertigo” have “survived the test of time and may be found in the literature today.” They recommend that the provider rule out “rotational vertebral artery syndrome,” and state:

“Once potentially severe causes of the symptoms have been ruled out, the most appropriate strategy seems to be use of manipulative and vestibular physical therapy.”

In 2014, researchers from the University of Montreal assessed 25 subjects with cervicogenic dizziness and 25 subjects with labyrinthine dizziness to determine which clinical tests were best able to distinguish between the two groups. Their study was published in the journal Otology & Neurotology, and titled (15):

Evaluation of Para-clinical Tests in the Diagnosis of Cervicogenic Dizziness

These authors concluded subjects with cervicogenic dizziness were more likely to:

- Have a sensation of drunkenness and lightheadedness.

- Have pain induced during the physical examination of the upper cervical vertebrae.

- Have an elevated joint position error during the cervical relocation test.

Treatment

There is strong evidence spanning decades, arising from multiple countries, and published in a variety of well-respected peer reviewed medical journals indicating that the reason for cervical vertigo is a mechanical lesion/dysfunction of the cervical spine. This lesion may be articular, capsular, ligamentous, muscular, or a combination there of. The strongest evidence is that the lesion/dysfunction is in the upper cervical spine, from C1-C3. Consequently, a variety of mechanical approaches to treatment of cervical vertigo have been assessed and the results are usually quite favorable.

These mechanical therapies include physiotherapy, varieties of passive joint mobilizations, manipulation, and muscle work. This same type of mechanical therapeutic approach is also effective in treating spinal pain conditions. The explanation for this is that the improvement in mechanical function creates a neurological sequence of events that closes the “Pain Gate.” (16)

The studies below review some of these mechanical approaches and their effectiveness is duly noted:

In 1996, providers from the Department of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology, University Hospital, Lund, Sweden, completed a prospective, randomized, controlled trial of 17 individuals with dizziness of suspected cervical origin and 17 healthy control subjects. The study was published in Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation and titled Postural and symptomatic improvement after physiotherapy in patients with dizziness of suspected cervical origin (17).

The subjects in this study suffered from both dizziness and neck pain. The treatment targeted their neck pain, yet measurement outcomes assessed their pain and dizziness, specifically using posturography body sway, the Visual Analog Scale ratings, and intensity/frequency of dizziness score. The authors concluded:

“Physiotherapy significantly reduced neck pain and intensity and the frequency of dizziness, and significantly improved postural performance.”

“Patients with dizziness of suspected cervical origin are characterized by impaired postural performance. Physiotherapy reduces neck pain and dizziness and improves postural performance. Neck disorders should be considered when assessing patients complaining of dizziness.”

In 1998, an article appeared in the European Spine Journal titled Vertigo in Patients with Cervical Spine Dysfunction(18). The authors defined “dysfunction” as a reversible, functional restriction of motion of an individual spinal segment or as articular malfunction presenting with hypomobility. The authors also state that upper cervical spine dysfunctions can cause vertigo, and they cite 13 references to support the premise. They explain vertigo may occur as a consequence of disturbances of proprioception from the neck. They cite an additional 4 references to claim that only dysfunctions of the upper cervical spine can cause vertigo, noting that anatomical studies identify links between upper cervical spine receptors and the vestibular nuclei.

In this study the authors used 50 patients who were referred to rule out a cervical spine problem as a cause of vertigo. All patients displayed symptoms of dizziness. Labyrinthine ear examination and neurology examination were equivocal. A reproducible manual palpation examining technique was used to diagnose segmental cervical spine dysfunction.

The cervical spine dysfunctions were treated with mobilization and manipulative techniques over a period of 3 months. Seventy-seven percent of the patients reported meaningful improvement in their vertigo, including 16% whose symptoms completely resolved. The authors state the following conclusions:

“Physical therapy is more likely to succeed in reducing vertigo symptoms if these patients present with an upper cervical spine dysfunction that is successfully resolved by manual medicine prior to physical therapy.”

“In the presence of vertigo, our presented data suggests consideration of cervical spine dysfunctions, requiring a manual medicine examination of upper motion segments.”

“A non-resolved dysfunction of the upper cervical spine was a common cause of long-lasting dizziness in our population.”

In 2005, researchers from the University of Newcastle, Australia, published an article in Manual Therapy titled Manual therapy treatment of cervicogenic dizziness: A systematic review (19). The authors note, “in some people the cause of their dizziness is pathology or dysfunction of upper cervical vertebral segments that can be treated with manual therapy.” They proceeded to review 7 electronic databases to locate both randomized controlled trials and non-randomized controlled clinical trials, finding 9 studies that met their inclusion criteria. They concluded:

“A consistent finding was that all studies had a positive result with significant improvement in symptoms and signs of dizziness after manual therapy treatment.”

“Manual therapy treatment of cervicogenic dizziness was obtained indicating it should be considered in the management of patients with this disorder.”

There is a manual therapy mobilization technique called “sustained natural apophyseal glides” (SNAGs) that is often used to treat cervical vertigo patients. In 2008, the journal Manual Therapy published a study titled Sustained natural apophyseal glides (SNAGs) are an effective treatment for cervicogenic dizziness (20). This aim of the study was to determine the efficacy of sustained natural apophyseal glides (SNAGs) in the treatment of cervical vertigo.

The authors performed a double-blind randomized controlled clinical trial involving 34 participants with cervicogenic dizziness who were randomized to receive four to six treatments of SNAGs (n=17) or a placebo (n=17). All were followed at 6- and 12-weeks. The authors concluded:

“The SNAG treatment had an immediate clinically and statistically significant sustained effect in reducing dizziness, cervical pain and disability caused by cervical dysfunction.”

This same group continued to assess the sustained natural apophyseal glides (SNAGs) protocol for patients with cervical vertigo and have reported similar conclusions (#21 in 2014 and #22 in 2015).

In 2013, chiropractors from the University of Zürich and Orthopaedic University Hospital Balgrist, Zürich, Switzerland, published a study in the journal Chiropractic Manual Therapy, titled Comparison of outcomes in neck pain patients with and without dizziness undergoing chiropractic treatment (23). The purpose of this study was to compare clinical outcomes of neck pain patients with and without dizziness undergoing chiropractic treatment. It was a prospective cohort study comparing neck pain patients with dizziness (n = 177) to neck pain patients without dizziness (n = 228).

Eighty percent of patients with dizziness and 78% of patients without dizziness were improved at 6 months. The authors concluded:

“Neck pain patients with dizziness reported significantly higher pain and disability scores at baseline compared to patients without dizziness. A high proportion of patients in both groups reported clinically relevant improvement.”

In 2015, physicians Yongchao Li, MD, and Baogan Peng, MD, PhD, from Liaoning Medical University, Beijing, China, published a study in the journal Pain Physician titled Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Cervical Vertigo (24). In this article they detail a syndrome they call “Proprioceptive Cervical Vertigo,” in which abnormal afferent input to the vestibular nucleus from damaged joint receptors in the upper cervical region alter vestibular function resulting in cervical vertigo. They note that this syndrome often occurs from whiplash trauma, noting:

“In whiplash-associated disorder, pain, limitation of movement, and strains of joint capsules, paravertebral ligaments, and cervical musculature could modify the proprioceptive cervical balance in a sustained way and produce mild but chronic vertigo.”

There are “close connections between the cervical dorsal roots and the vestibular nuclei with the neck receptors (such as proprioceptors and joint receptors), which played a role in eye-hand coordination, perception of balance, and postural adjustments. With such close connections between the cervical receptors and balance function, it is understandable that traumatic, degenerative, inflammatory, or mechanical derangements of the cervical spine can affect the mechanoreceptor system and give rise to vertigo.”

“Evidence leads to the current theory that cervical vertigo results from abnormal input into the vestibular nuclei from the proprioceptors of the upper cervical region.”

“Manual therapy is recommended for treatment of proprioceptive cervical vertigo.”

“Manual therapy is effective for cervical vertigo.”

“Cervical spondylosis and cervical muscle spasms can also cause vertigo.”

These authors note that if a patient has a chief complaint of vertigo, but no neck pain, a diagnosis of cervical vertigo is excluded. Cervical vertigo patients usually have pain in the back of the neck and occipital region, sometimes accompanied by neck stiffness. Cervical vertigo is often increased with neck movements or neck pain and decreased with interventions that relieve neck pain. The vertigo symptoms can be reproduced with head/neck movement. Pain is often elicited with palpation of the suboccipital region, cervical transverse processes of C1 and C2, cervical spinous processes of C2 and C3, levator scapulae, upper trapezius muscle, splenius, rectus, and semi-spinalis muscles.

The neck torsion nystagmus test may identify cervical vertigo: the head of the patient is stabilized while the body is rotated underneath.

Since cervical vertigo originates from proprioceptive dysfunction of the upper cervical spine, treatment should be to the upper cervical spine. Chiropractic and other manual spinal therapies have been shown to be effective in treating cervical vertigo, typically with around 80% acceptable clinical outcomes.

Another effective technique for treating cervical vertigo is a type of spinal mobilization known as “sustained natural apophyseal glides” (SNAGs), often resulting in significant immediate and sustained effect in reducing dizziness and neck pain. It restores “normal movement of the zygapophyseal joints, reducing pain and muscle hypertonicity, and thereby restoring normal proprioceptive and biomechanical functioning of the cervical spine.”

Summary

Hundreds of studies over the past 60 years have established that dysfunctions of the joints and/or muscles of the cervical spine, especially the upper cervical spine, can cause the sensation of vertigo. Neuroanatomical evidence shows that upper cervical spine mechanoreceptors/proprioceptors fire to the vestibular nucleus as a portion of our human upright balance mechanisms. These studies also link the functional neurophysiology of upper cervical spine mechanoreceptors/proprioceptors to the vestibular nucleus.

The upper cervical spine is anatomically unique, with great mobility coupled with reduced stability. Hence, it is especially vulnerable to trauma, especially whiplash-type trauma, and capable of initiating cervical vertigo.

Chiropractors are exceptionally trained in the diagnosis and treatment of cervical vertigo. This includes ruling out other potential causes for the vertigo symptoms. The safe and appropriate management of cervical vertigo requires training and skill, issues that are stressed in the education of the modern chiropractor. Chiropractic spinal adjusting (specific manipulation), and other treatment adjuncts, are safe and very effective in treating patients with cervical vertigo.

REFERENCES

- Epley JM; The canalith repositioning procedure: for treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo; Otolaryngology Head Neck Surgery; September 1992; Vol. 107; No. 3; pp. 399-404.

- Baloh R, Honrubia V; Clinical Neurophysiology of the Vestibular System; Third edition; Oxford University Press; 2001.

- Jordan P, Ramon Y; Nystagmus and Vertigo Produced by Mechanical Irritation of the Temporomandibular Joint-space; J Laryngol Otol; August 1965;79; pp. 744-8.

- Morgan DH; Temporomandibular joint surgery. Correction of pain, tinnitus, and vertigo; Dent Radiogr Photogr; 1973;46(2); pp. 27-39.

- Wright EF; Otologic symptom improvement through TMD therapy; Quintessence International; October 2007;38(9):e564-71.

- de Jong PT, de Jong JM, Cohen B, Jongkees LB; Ataxia and nystagmus induced by injection of local anesthetics in the Neck; Annals of Neurology; March 1977; Vol. 1; No. 3; pp. 240-246.

- NCMIC Chiropractic Solutions; Current Concepts in Spinal Manipulation and Cervical Arterial Incidents; 2006

- Ryan GM, Cope S; Cervical vertigo; Lancet; December 31, 1955;269(6905); pp. 1355-8.

- Hinoki M; Vertigo due to whiplash injury: a neurotological approach; Acta Otolaryngology; Supplement 1984;419; pp. 9-29.

- Luxon L; “Posttraumatic Vertigo” in Disorders of the Vestibular System; edited by Robert W. Baloh and G. Michael Halmagyi; Oxford University Press; 1996.

- Brandt t, Bronstein M; Cervical Vertigo; Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry; July 2001; Vol. 71; No. 1, pp. 8-12.

- Humphreys KM, Bolton J, Peterson C, Wood A; A Cross-Sectional Study of the Association Between Pain and Disability in Neck Pain Patients with Dizziness of Suspected Cervical Origin; Journal of Whiplash & Related Disorders, Vol. 1; No. 2; 2002, pp. 63-73.

- Treleaven J, Jull G, Sterling M; Dizziness and Unsteadiness Following Whiplash Injury: Characteristic Features and Relationship with Cervical Joint position Error; Journal of Rehabilitative Medicine; January, 2003; 35; pp. 36–43.

- Yacovino DA; Cervical vertigo: myths, facts, and scientific evidence; Neurologia; September 13, 2012.

- L'Heureux-Lebeau B, Godbout A, Berbiche D, Saliba I; Otology & Neurotology; Evaluation of para-clinical tests in the diagnosis of cervicogenic dizziness; December 2014; Vol. 35; No. 10; pp. 1858-1865.

- Kirkaldy-Willis WH, Cassidy JD; Spinal Manipulation in the Treatment of Low back Pain; Canadian Family Physician; March 1985; Vol. 31; pp. 535-540.

- Karlberg M, Magnusson M, Malmström EM, Melander A, Moritz U; Postural and symptomatic improvement after physiotherapy in patients with dizziness of suspected cervical origin; Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation; September 1996; Vol. 77; No. 9; pp. 874-82.

- Galm R, Rittmeister M, Schmitt E; Vertigo in patients with cervical spine dysfunction; European Spine Journal; July 1998; pp. 55-58.

- Reid SA, Rivett DA; Manual therapy treatment of cervicogenic dizziness: a systematic review; Manual Therapy; February 2005; Vol. 10; No. 1; pp. 4-13.

- Reid SA, Rivett DA, Katekar MG, Callister R; Sustained natural apophyseal glides (SNAGs) are an effective treatment for cervicogenic dizziness; Manual Therapy; August 2008; Vol. 13; No. 4; pp. 357-366.

- Reid SA, Rivett DA, Katekar MG, Callister R; Comparison of mulligan sustained natural apophyseal glides and maitland mobilizations for treatment of cervicogenic dizziness: a randomized controlled trial; Physical Therapy; April 2014; Vol. 94; No. 4; pp. 466-76.

- Reid SA, Callister R, Snodgrass SJ, Katekar MG, Rivett DA; Manual therapy for cervicogenic dizziness: Long-term outcomes of a randomised trial; Manual Therapy; February 2015; Vol. 20; No. 1; pp. 148-56.

- Humphreys BK, Peterson C; Comparison of outcomes in neck pain patients with and without dizziness undergoing chiropractic treatment: a prospective cohort study with 6 month follow-up; Chiropractic Manual Therapy; January 7, 2013; Vol. 21; No. 1.

- Li Y, Baogan Peng B; Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Cervical Vertigo; Pain Physician July/August 2015; 18:E583-E595.